真正第一代手提無線電話, 19 世紀發明:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nathan_Stubblefield

Inventions

Bob Lochte (2001) has argued that when Stubblefield spoke

of "wireless" telephony in the 1880s he merely meant his acoustic

telephone, which could operate with string. However, in the 1880s, Scientific American

had already carried articles describing attempts at wireless telephony

and telegraphy experiments by induction systems of Trowbridge, Preece,

Phelps, and Edison, not using high frequency radio waves, so

Stubblefield was likely familiar with all the principles needed to

operate wireless telephony by induction in the 1880s. He made

private demonstrations of wireless telephony in 1892. Rainey T. Wells

was one of the first persons to hear Stubblefield's wireless voice

transmissions, in that year. Wireless telegraphy using damped high frequency radio waves was demonstrated in 1894 by Sir Oliver Lodge, but that system could not carry voice messages or music. In 1898, Stubblefield was issued U.S. Patent 600457 for an "Electric battery,"

which was an electrolytic coil of iron and insulated copper wire to be

immersed in liquid or buried in the ground, where it could also serve as

a ground terminal for wireless telephony.

http://www.nathanstubblefield.com/contents.html

Wireless in 19th Century America -

Beginning with Morse's 1842 experiments, American inventors including

Bell and Edison confront the challenge of wireless telegraphy and

telephony with limited success. By 1891, most of them have abandoned

their efforts.

"Hello, Rainey." - In 1892, ignorant of

the wireless inventions of the past 60 years, Nathan creates an

electromagnetic induction wireless telephone and demonstrates it to his

friend Rainey Wells. A few years later, Nathan develops a superior

wireless telephone that uses natural conduction through the earth and

water.

The Wireless Telephone Company of America

- After a well-publicized public demonstration of his wireless

telephone on New Years Day 1902 in Murray, including its broadcasting

capabilities, Nathan's work attracts national attention. He follows this

event with a demonstration in Washington DC, where he makes a ship to

shore telephone call, and eventually accepts an offer of cash and stock

to sell his invention to the Wireless Telephone Company of America. The

company sends Nathan and his eldest son Bernard to Philadelphia and then

New York to demonstrate the system for wealthy potential investors. The

first presentation is successful, but the New York demonstration is a

failure. Nathan returns to Murray to expose the company as a fraudulent

stock promotion scheme.

...

Ada Mae, Pattie, and Nathan Stubblefield (l. to r.) with portable wireless telephone receiver, 1907

http://earlyradiohistory.us/1902stb.htm

Scientific American, May 24, 1902, page 363:

THE LATEST ADVANCE IN WIRELESS TELEPHONY.

BY WALDON FAWCETT.

The

latest and one of the most interesting systems of wireless

communication with which experiments have recently been conducted is the

invention of Nathan Stubblefield, of Murray, Ky., an electrical

engineer who is the patentee of a number of devices both in this country

and abroad. The Stubblefield system differs from that originated by =

Marconi in that utilization is made of the electrical currents of the

earth instead of the ethereal waves employed by the Italian inventor,

and which, by the way, it is now claimed, are less powerful and more

susceptible to derangement by electrical disturbances than the currents

found in the earth and water. In this new system, however, as in that

formulated by Marconi, a series of vibrations is created, and what is

known as the Hertzian electrical wave currents are used.

The key to the methods which form the basis of all

the systems of wireless telephony recently discovered--the fundamental

principles of wireless telephony, as it were--was discovered at

Cambridge, Mass., in 1877 by Prof. Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor

of the telephone system which bears his name. On the occasion mentioned

Prof. Bell was experimenting to ascertain how slight a ground connection

could be had with the telephone. Two pokers had been driven into the

ground about fifty feet apart, and to these were attached two wires

leading to an ordinary telephone receiver. Upon placing his ear to the

receiver, Prof. Bell was surprised to hear quite distinctly the ticking

of a clock, which after a time he was able to identify, by reason of

certain peculiarities in the ticking, as that of the electrical

timepiece at Cambridge University, the ground wire of which penetrated

the earth at a point more than half a mile distant.

Some five years later Prof. Bell made rather extensive experiments

along this same line of investigation at points on the Potomac River

near Washington, but these tests were far from satisfactory. It was

found on this occasion that musical sounds transmitted by the use of a

"buzzer" could be heard distinctly four miles distant, but little

success was attained in the matter of communicating the sound of the

human voice. Meanwhile Sir William Preece, of England, had undertaken

experimental study of the subject of wireless telephony, and during an

interval when cable communication between the Isle of Wight and the

mainland was suspended, succeeded in transmitting wireless messages to

Queen Victoria at Osborne by means of the earth and water electrical

currents.

Mr. Stubblefield's experiments with wireless

telephony dated from his invention of an earth cell several years ago.

This cell derived sufficient electrical energy from the ground in the

vicinity of the spot where it was buried to run a small motor

continuously for two months and six days without any attention whatever.

Indeed, the electrical current was powerful enough to run a clock and

several small pieces of machinery and to ring a large gong. Mr.

Stubblefield's first crude experiments looking to actual wireless

transmission of the sound of the human voice were made without ground

wires. Nevertheless, by means of a cumbersome and incomplete machine,

without an equipment of wires of any description, messages were

transmitted through a brick wall and several walls of lath and plaster.

As the development of the system progressed, the present method of

grounding the wires was adopted, in order to insure greater power in

transmission.

<>

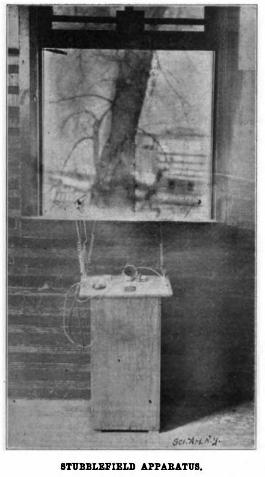

The apparatus which has been used in the most recent

demonstrations of the Stubblefield system, and which will be installed

by the Gordon Telephone Company, of Charleston, S. C., for the

establishment of telephonic communication between the city of Charleston

and the sea islands lying off the coast of South Carolina, consists

primarily of an ordinary receiver and transmitter and a pair of steel

rods with bell-shaped attachments which are driven into the ground to a

depth of several feet at any desired point, and which are connected by

twenty or thirty feet of wire to the electrical apparatus proper. This

latter consists of dry cells, a generator and an induction coil, and the

apparatus used in most of the experiments thus far made has been

incased in a box twelve inches in length, eight inches wide and eighteen

inches in height. This apparatus has demonstrated the capability of

sending out a gong signal as well as transmitting voice messages, and

this is, of course, of great importance in facilitating the opening of

communication.

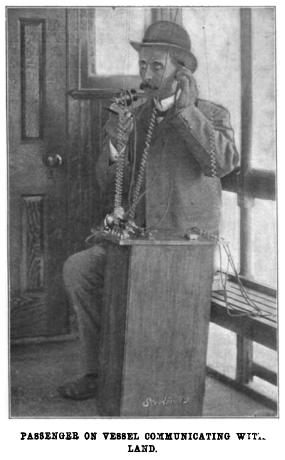

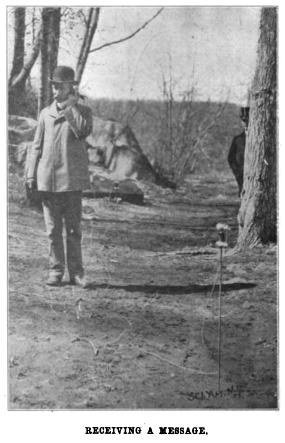

The most interesting tests of the Stubblefield system

have been made on the Potomac River near Washington. During the land

tests complete sentences, figures, and music were heard at a distance of

several hundred yards, and conversation was as distinct as by the

ordinary wire telephone. Persons, each carrying a receiver and

transmitter with two steel rods, walking about at some distance from the

stationary station were enabled to instantly open communication by

thrusting the rods into the ground at any point. An even more remarkable

test resulted in the maintenance of communication between a station on

shore and a steamer anchored several hundred feet from shore.

Communication between the steamer and shore was opened by dropping the

wires from the apparatus on board the vessel into the water at the stern

of the boat. The sounds of a harmonica played on shore were distinctly

heard in the three receivers attached to the apparatus on the steamer,

and singing, the sound of the human voice counting numerals, and

ordinary conversation were audible. In the first tests it was found that

conversation was not always distinct, but this defect was remedied by

the introduction of more powerful batteries. A very interesting feature

brought out during the tests mentioned was found in the capability of

this form of apparatus to send simultaneous messages from a central

distributing station over a very wide territory.

Extensive experiments in wireless telephony have also

been made by Prof. A. Frederick Collins, an electrical engineer of

Philadelphia, whose system differs only in minor details from that

introduced by Mr. Stubblefield. In the Collins system, instead of

utilizing steel rods, small zinc-wire screens are buried in the earth,

one at the sending and another at the receiving station. A single wire

connects the screen with the transmitting and receiving apparatus,

mounted on a tripod immediately over the shallow hole in which the

screen is stationed. With the Collins system communication has been

maintained between various parts of a large modern office building, and

messages have been transmitted without wires across the Delaware River

at Philadelphia, a distance of over a mile.